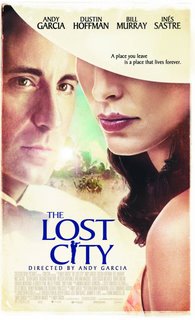

Finally got to see The Lost City directed by Andy Garcia. Words can not describe the emotions one feels while watching the movie. Where do I begin? I am going to be honest with you, I was not expecting much nor the reaction my wife and I had(tears)! I want to watch it again because I missed some scenes due to my emotions. The couple sitting next to us kept looking at us and wondering? I am not a film critic nor pretend to be one, but Andy Garcia did a wonderful job and has to be commended for all his efforts and persistence concerning the refusal of Hollywood to produce this movie.

I hope this leads to more movies concerning the "real" happenings of the Cuban situation. We need a movie concerning the heroes in the Escambray Mountains, a movie concerning all the political prisoners, a movie concerning the exile experience, and so many topics that have not been even touched!

This gives me even more admiration for my parents and family on what they went through. Cuban exiles are given a bad rap by the media.The media and critics never saw the heartache, the pain inflicted by the absurdity of communism and the obvious attack on the family by the dictator. The critics never had to endure the pain while leaving your beloved country and getting on a airplane, the commie soldier telling you not to look back at your family or you will not be allowed to leave the country after rummaging through all your things. The critics have never had to endure the pain of family members being imprisoned or tortured simply on their beliefs! The critics have never had to endure some punk commie stealing the farm or property in the name of the revolution. The critics have never had to endure the pain of someone who you love dearly, for years watching every blip of news with a glimpse of hope waiting for the downfall of the dictator. I can see it in his eyes, though never spoken, I wish I could ease his pain and yearning for a FREE Cuba. The emotions of that person telling me with pride of his hometown and the fond memories and that he might not ever go back, but that I one day will go!

How do you describe that to someone that does not comprehend the Cuban experience?

The dignity and pride shown even with all the obstacles they faced is extraordinary and admirable. The dictator tried to destroy Cuba and the Cuban family, but he did not succeed! The bonds of family and our almighty God will never be defeated!

So media and critics: The real heroes in my book are my parents and my family. The real heroes are those who have died yearning for a FREE Cuba.

Excuse me while I wipe away a tears!!!

Truly well said, Alfredo. Your post encapsulates many if not all of the emotions and experiences so many of us have on the subject.

ReplyDeleteI cant wait to see it..

ReplyDeleteThey are showing it in Puerto Rico now.

I will go this week

Some of my relatives saw it today...

I'm glad you enjoyed the film

ReplyDeleteAlfredo,

ReplyDeleteI parallel your sentiments. I saw it a while ago, and have not written about it because others like you have done it and have done it better than I ever could. Thank you for your valued post.

The Lost City portrayed the sad reality of Cuban politics and the deceit and evilness of a victorious Leninist revolution.

ReplyDeleteWe too, my wife and I, were overwhelmed by the many memories of what once was.

I have ordered, through Barnes & Nobles in Coral Gables, Fl., the DVD and the CD for the movie. I understand that the DVD will be out in August and the CD next month.

To all my countrymen: Keep the faith up. Next year in a free Cuba.

Alfredo,

ReplyDeleteoutstanding... You brought tears to my eyes!

Alfredo,

ReplyDeleteVery emotional post and I commend you! Keep blogging my friend you are a inspiration.

El Cartagenero

Who cares?

ReplyDeleteViva La Raza-----

The Lost City: Andy Garcia’s business message to Cuba

ReplyDeleteBy Saul Landau

from www.progresoweekly.com

For decades, Florida-based exiles claimed they had a better model to offer than the island’s revolutionaries. Thanks to Andy Garcia, that alternative becomes clear: freedom to do business, uber alles. Garcia “dreamed” of making this film while, simultaneously, millions of Latin American migrants “dreamed” of coming to the United States, to find sub-minimum wage jobs. Cubans, however, could claim legal residency by placing a professed anti-Castro toe on U.S. soil. By passing the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act, Congress offered Cubans pretending to “escape from Castro’s tyranny” an exclusive path to a U.S. green card. Others fled a political system they found repugnant.

Congress reacted to Fidel “The Guinness World Record Holder for Disobedience” Castro, who somehow planted an invisible virus into the punitive liver of the U.S. elite, one that induced a flow of bile to its unforgiving brain. For 47 years, Castro’s defiance has provoked irrational U.S. behavior. This irrationality now has an aesthetic side. Anti-Castroism makes another screen debut as “The Lost City,” in which Garcia’s vacuous “reveries” take shape as film characters.

Garcia produced, directed, co-wrote and, coincidentally, stars as Fico, one of three upper middle class Fellove brothers. He owns a Havana night club in 1958, but doesn’t allow gambling, a unique – if unbelievable – occurrence in that era.

The film shows Batista’s police killing, torturing and intimidating. It doesn’t show the U.S. government continuing to support the dictator – surreptitiously after his human rights record became front page news in the New York Times. The script follows the Fellove family as Papa presides over traditional Sunday dinner. He demands punctuality, a heavy metaphor for the good, old ways. Parents, three sons, one of their wives, and a tubby uncle, a comic relief figure, enjoy the ritual.

After dinner, men discuss revolution with brilliant lines. “I believe in evolution not revolution.” No one mentions the United States had economically colonized Cuba, that the Cubans’ struggle for independence, begun in the 1860s, remained unrealized.

Instead, the script throws in famous incidents and names. Revolutionaries kidnap Argentine race car driver, Fangio – we don’t learn why – and Meyer Lansky, whom Dustin Hoffman plays as a rabbinical gangster, tries to lure virtuous Fico into his gambling racket. Later, someone bombs Fico’s club, leading us to suspect Lansky. In 1960 New York, Fico sees Lansky again. The avuncular Jewish mobster assures Fico, “It wasn’t me, boichik.”

So who was it? The film doesn’t answer. But it teaches lessons about Cuba and freedom. The film’s moral: an honest nightclub owner couldn’t stay in business in revolutionary Cuba because arrogant Castroites objected to the saxophone as “an instrument of the imperialists.” (Not bourgeois corruption?) In free New York, Fico realizes his movie dream: he opens a club and presumably lives happily ever after.

Fico fails in love, however. After his assassination-minded brother dies at the hands of Batista’s police, Fico comforts the gorgeous widow and becomes her lover. In the transition, Aurora, the grieving beauty (Inés Sastre, a Spanish model whose mood changes vary between dour and less dour) shows her modeling talent. She and Fico pose in different costumes, straw hats, casual beachwear, formal suits and gown-less evening straps – while sipping mojitos by the ocean. Is this what accompanies business freedom, expensive clothes in a country where one third of the population was literate?

Fico offers to save the “widow of the revolution” by taking her from the excitement and celebrity of her job to serve as his wife in the United States. She opportunistically chooses her professional life in Cuba over the chance to spend her life as Mrs. Nightclub Owner. Needless to say, Fico the Macho never considers changing his business plans for her career.

In the Spring of 1960, I met Guillermo Cabrera Infante, the film’s co-writer. Garcia, a tiny boy, wouldn’t remember those days just after the revolutionaries reversed their saxophone-banning policy, because Cabrera Infante and I went together to the Tropicana – Fico’s fictional “El Tropico?”

Near the Tropicana, posters referred to Eisenhower’s July 1960 cancellation of Cuba’s annual sugar quota. “Sin cuota pero sin amo (without a quota, but without a boss). Guillermo sneered: “Sin cuota pero sin ano.” (without a quota but without an asshole).

When the U.S. Congress voted for the quota they guaranteed purchase of Cuban sugar at a fixed price – a kind of insurance policy that also kept Cuba an economic prisoner. That day, Cabrera Infante and I listened to Cuban jazz combos – each with a sax player.

Guillermo edited Lunes de Revolucion, the literary supplement of Revolucion, the 26 of July Movement’s official organ. Lunes published existentialists, beat poets, Trotsky and Brecht.

Other non-government newspapers were also published at that time, although from seeing “The Lost City” one wouldn’t know of this early revolutionary excitement. In early 1961, after thousands of terrorist attacks from the United States, the revolution turned hard and began to prepare for the inevitable invasion (which came at the Bay of Pigs in April 1961).

The free-wheeling cultural scene tightened. Lunes disappeared and with it, the diversity that Cuba’s literary public enjoyed for the first two revolutionary years. Guillermo went to Brussels as cultural attaché, defected in 1964, and died a bitter man in 2005. Cabrera Infante loved film noire, however, not film ecru.

I can’t imagine him writing boring scenes about the anti-Batista insurrection. In 1958, when the film opens, Fidel Castro and his guerrillas had seized the military initiative. The urban underground wreaked havoc with Fulgencio Batista’s “order.” The film, nevertheless, focuses on dull Fellove family scenes.

Garcia’s “dream” turns quickly vapid, disintegrating into costume changes and random inter-cutting of hot music and dance numbers – a relief when the dialogue and plot grow too ponderous to bear. Batista’s brutality falls into a predictable Hollywood violence scene with stereotyped black hats; the evil revolution emerges as a cruel Che Guevara (Jsu Garcia).

But “The Lost City” (“The Mislaid Script”) does not place its characters in settings from which audiences can understand events outside them or the reason for their behavior. For example, Fico proclaims: “Everything I do, I do for my family.” Tony Soprano could use that line. “There's no happiness outside the revolution,” says a revolutionary brother. Sounds like a college parody of socialist realism!

Garcia’s fictional family lacks the intricate subtleties possessed by real sibling relationships. One brother (Nestor Carbonell) opts to assassinate Batista (Juan Fernández); another (Enrique Murciano) joins Fidel’s guerrillas in the Sierra. Fico manages his nightclub and intervenes in family arguments. “It is disrespectful to disagree with Papa,” who claims he believes in free speech.

The slimy Batista, a central casting black hat, escapes assassination. The Fellove brother dies. Batista flees with his ill-gotten wealth and the new villains arrive in Havana. Garcia’s treacherous Che vitiates the saintly poster boy of college dorm rooms. Power-obsessed, Che kills without hesitation and delights in psychological cruelty. The portly uncle of the dinner ritual owns a large tobacco plantation. The bearded Argentine doctor dispatches the fidelista Fellove to expropriate his uncle’s holdings. The overweight man suffers a heart attack, which shames the errant revolutionary; so he kills himself.

To counter the tragedy, Bill Murray slides into the script as a witty Greek chorus – well, he has one or two sort of funny lines. Perhaps he represented Cabrera Infante’s last puns! He does little, however, to redeem “The Lost City.”

The film’s lesson is quintessentially banal: freedom for business is good; the Cuban revolution destroyed private ownership, therefore it is bad. After the saxophone-hating revolutionaries shut down Fico’s club in Havana, the United States let him open a club in New York – after doing a brief stint as a dishwasher.

Ultimately, that’s what virtue means to Garcia and his character. “‘The Lost City’ unravels as a totem to lost wealth,” wrote Ed Gonzalez (Slant 2006). “A manifesto that will likely appeal only to those Cubans whose bank accounts were splintered after the revolution, or those who’ve managed to make a fortune in the United States.”

The film shows Fico’s pretensions to idealism as a dislike for Batista’s cops. But he doesn’t rebel against their torture and death tactics. He demonstrates his contempt for Che by throwing a glass at him at a party. Ultimately, Fico cares about his property and the privilege that accrue to those holdings. His superior, indeed, smug look, are a façade for a man without values.

“Watching the film,” Gonzalez concluded, “you’d think all of Cuba was living in the lap of luxury before Castro came along.” “[I]magine poor, black Cubans trying to break through the pearly gates of this Lost City, which has the gloss of a non-inclusive commemorative stamp.” Garcia’s film hero doesn’t think about “freedom” for poor Cubans. For Fico, freedom is narrow. It means a government that allows him to run his own nightclub. Go for it, Fulanito!

Landau is an Institute for Policy Studies fellow.

Viva Cuba Libre

ReplyDelete